Communities of color have experienced a long history of being lynched. As recently as last fall, a migrant man from Mexico was found dead in Texas in an apparent lynching. Now, a new law finally makes this act of terror a federal hate crime.

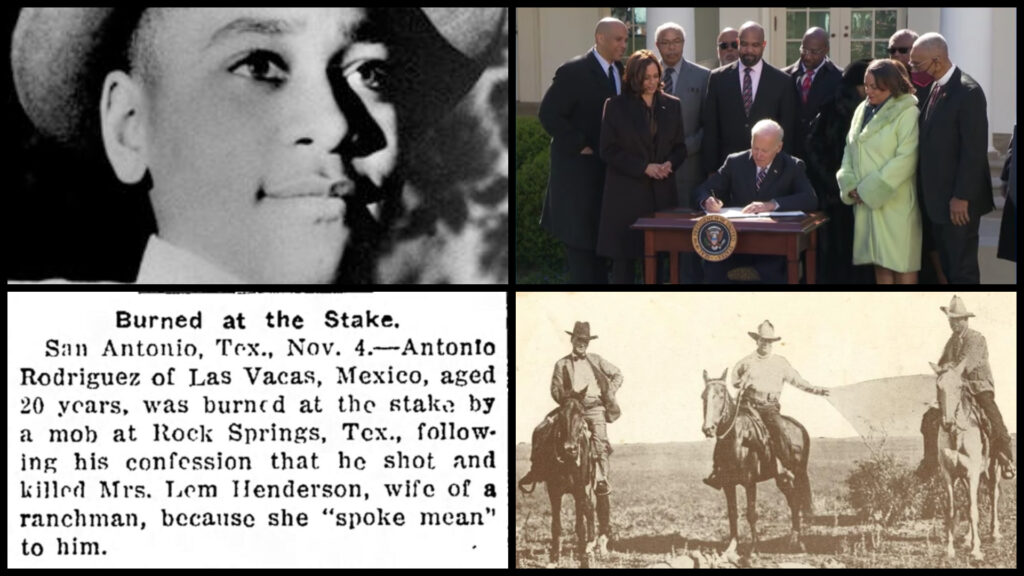

The Emmett Till Anti-lynching Act was signed into law by President Joe Biden this spring. The bill was named after a 14-year-old Black boy from Chicago who died in 1955. He was kidnapped, tortured and killed by a mob of white men in Mississippi after allegedly whistling at a white woman. His murder sparked a national outcry.

“Lynching was pure terror to enforce the lie that not everyone — not everyone belongs in America and not everyone is created equal,” Biden said.

What exactly is lynching? “Lynching typically is understood to mean illegal mob actions that result in the slaying of a person based on race without due process for the victim,” the L.A. Times explains. The NAACP describes lynching as “public violent acts that white people used to terrorize and control Black people in the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in the South.”

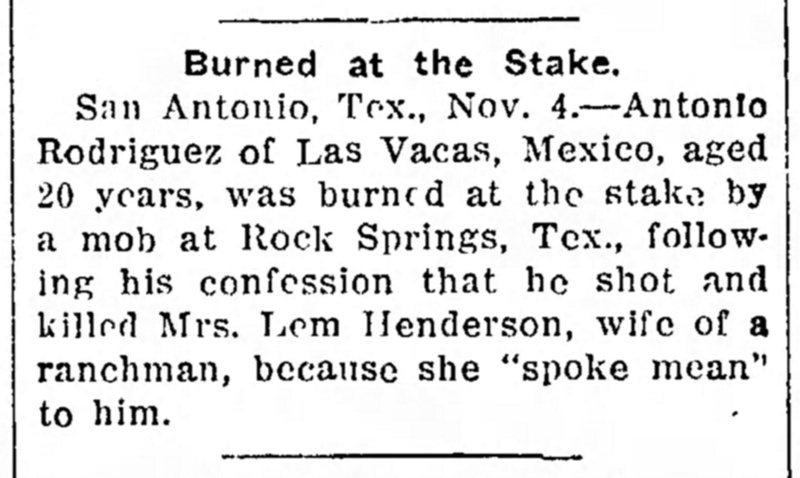

A report by the Equal Justice Initiative shows that there were more than 4,400 terror racial lynchings in the country in the period after the Civil War through World War II. While Black people accounted for 72% of lynchings, immigrants from Mexico, China and other countries were also lynched.

Examples of anti-Latino lynchings include:

In 1896, Aureliano Castellán was executed for looking at a white woman. His body was found severely burned, with eight bullet wounds. His attackers had poured coal oil on him, and burned his body before dumping it into the river.

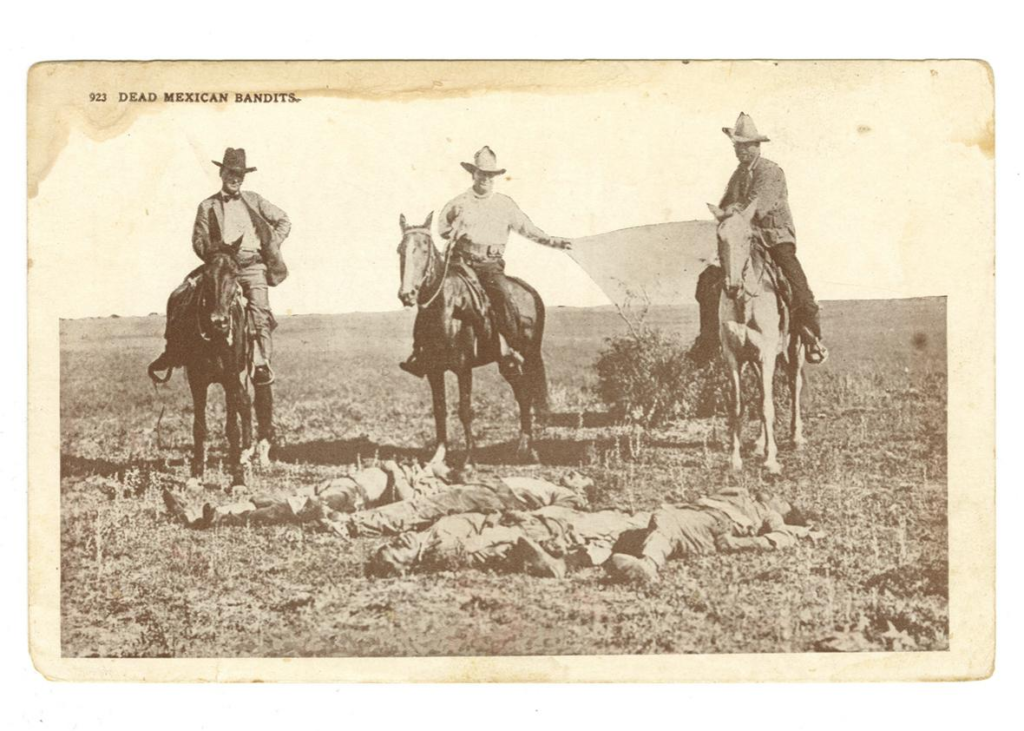

In 1910, Antonio Rodriguez was jailed, accused of murdering a rancher. An angry mob swarmed the jailhouse, torturing 20-year-old Rodriguez before burning him alive.

In 1911, Antonio Gomez, age 14, was approached by a mob that accused him of a crime, and encircled him before he could get away. In an act of self defense, he stabbed one of the men, who later died. Within three hours, Antonio was jailed, abducted, dragged by chain and hanged.

And lynchings of Latinos have continued even in modern times. In October, Pulso informed you about an apparent lynching in Brooks County, Texas, where a Mexican migrant man was found dead, hanging from a tree. The victims’ clothes were located nearby and his feet were missing.

Prior to the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, previous attempts had been made to get anti-lynching legislation passed, but the filibuster prevented them from becoming law.