In the wake of stringent US immigration policies, at least 138 Salvadorans have been killed following their deportations. The US is repeatedly violating its obligations to protect Salvadorans from return to serious risk or harm. Photo: David Stanley, Cemetery in San Miguel, El Salvador, CC BY 2.0

A recent human rights report and video footage detail how Central American migrants are brutally victimized abroad and on American soil due to draconian immigration policies. As the United States tightens restrictions on asylee entries, the report shows that many migrants who are deported are being assaulted, raped, and killed, and many held at detainment centers also face abuses and misstreatment.

Human Rights Watch released a new report in February highlighting violence afflicting Salvadorans deported by the United States. Rampant gang violence in El Salvador, often motivating Salvadorans to seek asylum in the United States, has led to at least 138 documented murder cases since 2013. Many of the 200 cases in the report show a clear link between the killing or harm of a deportee, and the reason they initially fled El Salvador.

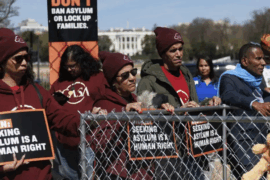

Photo: John Moore, Getty Images.

Gangs, like MS-13 (Mara Salvatrucha), are inflicting violence on some returned migrants for their perceived attempts of fleeing gang recruitment. One case includes the killing of Javier B. When the 23-year-old was denied asylum and returned to El Salvador in 2017, MS-13 targeted and killed him because of his tattoos. “They got him from the house at 11:00 a.m. They saw his tattoos. I knew they’d kill him for his tattoos. That is exactly what happened…” Jennifer B., Javier’s mother, said. Having tattoos may be a source of concern, even if the tattoo is not gang-related, according to Human Rights Watch research.

Other victims, like Angelina N. who was deported to El Salvador in 2014, fled her home country after being raped by multiple abusers. One of her abusers, gang member Mateo O., raped her at gunpoint and threatened to kill her father and daughter if she reported the rape to authorities.

Fear of gang violence has spurred a surge in asylum applications, leading the Trump Administration to institute new immigration policies that serve as entry barriers. The “Remain in Mexico” policy and the million case asylum backlog in the US have created pandemonium for migrants stuck in limbo at the border, and for those seeking American protection.

As asylum-seekers head to the border en masse, the United States made an agreement with Guatemala to remove the migrants, mostly women and children, off American soil in order to apply for asylum. But applicants are finding themselves either rushed into a hearing with no time to access counsel, or placed on a waiting list that can last up to two years. “Sometimes, things are too fast, and sometimes they’re too slow,” Gracie Willis, staff attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, said. “But what’s not happening is that cases are going forward when they’re ripe”.

Video footage depicting a 2017 detainee protest at a privately run US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention center in California highlights the violence undocumented Central Americans face while detained. The footage starts off with a detainee presenting a guard with a list of grievances, including access to clean water and no translation for materials presented to them in English.

When the guard alerts her supervisor of the grievances, the detainees remain seated at two tables after they had been instructed to return to their cells. The angered guards then pepper spray the detainees while they are huddled together with arms locked in solidarity. The guards then pry the detainees away from each other and continue to pepper spray them.

The clear and present dangers driving Central Americans to seek U.S. refuge is evident in the numbers. From 2012 to 2017, the number of asylum applications submitted by Salvadorans shot up by 1,000% and in 2018 the group led the list of asylum seekers with 101,000 pending applications on the backlog.