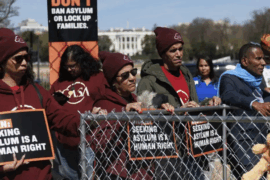

The “Remain in Mexico” policy has forced thousands of migrants to wait in border town camps as their asylum cases are decided, while teams of modern day “freedom riders” from across the country mobilize to bring them books to read, food to nourish their spirit, and a serving of camaraderie and hope.

The Mexican government rejected the Trump Administration’s proposal to send Mexican migrants to Guatemala to apply for asylum on Monday, Jan. 6. This is the latest episode in the long and arduous saga of the Migrant Protection Protocols, better known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy, that has forced 56,000 migrants to wait in makeshift border town camps while a legal determination is made on their asylum cases. While they await determinations on their U.S. immigration hearings, Americans from all walks of life have donated their time and resources to bring a semblance of comfort to the masses stuck at the border.

Since November, the U.S. has deported 96 Mexicans, Central and South Americans, and Cubans to Guatemala to apply for asylum. But the majority of asylum seekers have remained grouped into uncomfortable and crowded migrant camps in Mexico that often lack running water and indoor plumbing. In Matamoros and Nuevo Laredo, places the U.S. State Department has warned Americans to avoid because of high crime and kidnappings, the asylum seekers await news of their fates.

In response, volunteers from across the U.S. are flooding the border towns en masse to help the migrants in limbo. These modern day freedom riders are leading human rights efforts as the original freedom riders once did to combat racism and civil rights violations in segregated 1960s towns.

The volunteers come from diverse cities, like Columbus and San Francisco, and their various professional fields include law, education, and restaurant work. Local leaders are taking note of their selfless effort to make life a little better for the asylum seekers. “We’re here as brothers and sisters,” Sister Norma Pimentel, leader of the Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande, said “We’re also restoring and preserving our own humanity in the process.”

Volunteers are not just everyday Americans, they also include renowned artists such as New Mexican author Denise Chávez whose “Libros para el Viaje” initiative was launched to bring books to people in shelters and places of need. But when Chávez saw the effects of the “Remain in Mexico” policy, she focused her efforts on bringing books to migrants at the asylum camps. “We’re on a journey, all of us together as human beings,” Chávez said “We’re on that road and we need to reflect on the fact that we’re all familia.”

Now more than 50 bookstores from across the country have donated books to support Chávez’ initiative. One group of volunteers based in Minnesota launched the “Books for Border Kids” drive in a collaboration with Red Balloon Book and Wild Rumpus book shops to deliver over 3,000 books to children at the border.

As the crowds of asylum seekers wait for news of their immigration hearings, chefs from the World Central Kitchen have coalesced in Brownsville, Texas to train volunteers on how to cook for large crowds of people. Over the past few months, the volunteers known as “Team Brownsville”, had started taking food across the border into Matamoros to feed 2,500 migrants daily.

With the arrival of the World Central Kitchen team, the Brownsville-Matamoros operation has received a morale boost and professional training to expand the amount of people they can feed per day. “We’re here. We have our food truck. We have a team in place.” Tim Kilcoyne, chef at World Central Kitchen, said “We’re trying to integrate and work with Team Brownsville because they’ve done an amazing job and we just want to compliment them.”