Liz Alarcón: Dear Mexican. Why is it that when you invite Mexicans to a party, they feel compelled to bring along 30 of their relatives. mean, bringing along two or three people would be no problem, but we don’t expect the number of people at our party to double by inviting an extra person. Signed, not enough food for everyone. Gustavo answers, dear gabacho, Mexicans and parties? Was there ever a more spectacularly grotesque coupling. We drink mucho. We eat mucho. We fight mucho. We love mucho. We mucho, mucho. Examining the Mexican propensity to party Mexican Nobel Laureate Octavio Paz wrote, the explosive dramatic sometimes even suicidal manner in which we strip ourselves, surrender ourselves, is evidence that something inhibits and suffocates. Something impedes us from being. And since we cannot or dare not confront our own selves, we resort to a fiesta.

That was an excerpt from “Ask A Mexican” a hugely popular and longrunning column where readers could… “ask a Mexican” a question, no matter how ridiculous it may be.

Charlie Garcia: It’s such a beautifully poetic way to answer this ridiculous question.

Ray Aguilera: It is true though. We do show up to parties with a lot of extra people. Like I’m not going to pretend like that’s not real. I mean, you know, your cousin comes and their friends, everybody loves a party and the more, the merrier.

Liz Alarcón: The year was 2004. Gustavo Arellano was working at California’s OC Weekly, just your typical, bustling and busy newsroom. One random day, his editor Will, walked into the office and asked him a question

Gustavo Arellano: He’s like, hey, I just saw a billboard for the Spanish language DJ. And I’ve never heard of this guy before. He’s wearing a Viking helmet. He has it like his eyes are crossed and his names “pile-in”. Have you ever heard of “pile-in” before? I’m like, oh, you’re talking about El Piolín. Exactly.

Liz Alarcón: Of course.

Gustavo Arellano: and I said, you’re pretty stupid for not knowing who El Piolín is because he’s a big name and you’re being stupid. Not because you’re a white person and white people are supposed to know everything about Mexicans, but because you’re out of the editor of a big newspaper, you should know what’s going on in your backyard.

Liz Alarcón: That gave Will an idea… he needed more content for the newspaper, so he thought, why don’t we make a joke column where anyone can questions to a mexican person?!

Gustavo Arellano: I thought to myself, okay. I think this is a dumb idea because I don’t think people are gonna like it, but let’s just go. What’s the stupidest question someone could ask me about Mexicans?

Liz Alarcón: And that stupid question was…

Gustavo Arellano: It was the one that Will would ask me again and again. Oh, why do Mexicans call white people gringos? And my response was, well, dear gabachos. Only gringos call gringos, gringos and Mexicans actually call gringos gabachos.

Liz Alarcón: So they published the one time joke column on the following week’s edition of the paper, and included they’re own caricature along with it: a stereotypical bandido with a sombero and a gold tooth.

Gustavo Arellano: It was just like meta satirical all with the intention of ridiculing clueless gabachos. Not expecting anything out of it. I put my email at the very bottom. I said, Hey, if you have any spicy questions about Mexicans, ask them to me not thinking anyone ever would.

Liz Alarcón: But to Gustavo’s suprise, they did

Gustavo Arellano: The day that the column first publishes, which is Thursday, we got 50 questions like within hours. Immediately. And it wasn’t just, uh gabachos who were asking them, uh, it was everyone. Everyone had a question.

Liz Alarcón: That’s how ask a Mexican was born. Questions started pouring in and It became a twice a week column in the newspaper. It reached thousands of readers and shed light on all kinds of issues that those with Mexican heritage have to deal with, from innocent curious questions, to really offensive ones. Gustavo answered them all. And for him, this work was a kind of activism, a way to talk about his Mexican roots from the perspective of someone who grew up in California as the son of immigrants.

When did you realize that you were Mexican American, that you were bi-cultural? You talk a lot about that identity and I’m curious if there is a moment where you realized, oh, this is who I am.

Gustavo Arellano: I remember I’d get into these fights with, uh, my cousins and friends growing up all the way through high school. Nah, I’m American. I’m not Mexican. I’m American. I’m American. Yeah. My parents are Mexican, but I’m American, but the light switched on for me. When, one of the trustees for the high school district that I graduated from he announced that he wanted to sue Mexico for $50 million for educating the children of undocumented immigrants. And the reason was that people like me were ruining Anaheim schools and that just pissed me off to no end so that’s actually what pushed me into activism, which led into journalism There’s a quote by a legendary muralist He said, my idea of being an American is to be as Mexican as I want. And I’m like, yes, that’s exactly what it is. So that’s how I identify.

Liz Alarcón: Powered by this drive, Gustavo dug in and answered questions week after week.

Gustavo Arellano: I mean, I literally got everything. Horrible questions, hilarious questions. In the early days I would get a lot of racist questions, but you have to remember, like the columnist has the last laugh. The columnist has the last answer. So when people would ask racist questions, oh man, I would get at them with a, with a metaphorical baseball bat.

Liz Alarcón: And Gustavo elegantly & ruthlessly cut them to pieces, when one reader asked why cholos love old English fonts, and said “it’s ugly, like everything about your culture.” Gustavo responded: Dear racist, the popularity of old English script is a prison phenomenon that transcends race, just check out some of the tats on your white supremacist cousins next time they show up at your family picnic. But not all the racist questions were coming from white people

Gustavo Arellano: I would say I was most ruthless to, um, Mexicans who are racist against black folks. Uh, but anyone, I remember some idiot Mexicano starts talking all sorts of trash about central Americans. I’m like, oh man, your question is so dumb. You’re just as racist as people from the past. But in this case, you’re Mexican and you’re racist against central Americans. You should know better. Us as Mexicans being, we are the biggest group, we gotta be better than the gabachos being racist against other groups, especially central Americans. We’re not better than gabachos frankly were worse.

Liz Alarcón: If you’re new to the Pulso pod, you should know we tackle this issue often. We have a lot of soul searching to do when it comes to the anti-Black, anti-indigenous attitudes still present in the Latino community. As you all can imagine, when taboo topics are the them of the column, controversy follows.

Gustavo Arellano: Of course at anytime you write about Mexicans, anything, people are going to be upset. People who hate Mexicans, hated the column. People who liked Mexicans hated the column, but people who hated Mexicans, liked the column, people who liked Mexicans loved the column.

Liz Alarcón: But it wasn’t all controversy.

Gustavo Arellano: I can say though, that I got a lot dozens, if not hundreds of responses. Oh, thank you. Thanks for Ask A Mexican. It really taught me to be proud of my Mexican roots when I was in high school. I want to get more into Mexican culture. What are some books I should read? What are some activists I should follow? What should, what should it be some music I would follow?

Liz Alarcón: That’s a beautiful legacy Gustavo and I think one of the reasons why it was so successful is precisely that satirical tone that you took. Can you tell us more about why humor and why that was a mechanism to this debunking of stereotypes that you sought out with the column?

Gustavo Arellano: What I always loved about humor is that it was a great Eradicator. The powers that be, you could shoot at them. You could throw bricks at them. You could yell at them. You could protest at them. They don’t care. They don’t care. They’re always going to have bigger guns than you, bigger bricks and you all of that. What they can not stand ever is being ridiculed. In orange county, I covered a lot of hate groups like literal bonafide neo-Nazis and that’s where I quickly realized that, you know, making fun of them, they hated that. They’re used to the insults, but the humor, they’re not used to that because we’re supposed to be scared of them. Well, I was never scared of white supremacy, and I was never scared of calling out our own people for our, for our own stupidities. So if we’re, if I was going to do ask a Mexican as a commentary of how ignorant people were about Mexicans then yeah, I was going to use humor.

Liz Alarcón: Gustavo accomplishes so much with his humor! He educated people, connected his readers to their Mexican heritage, built a solid community that tackled discrimination, racism and injustice head on…all from his local newspaper. Words and stories really can create a long lasting change and leave a meaningful legacy of tolerance and celebrating diversity. That’s what Gustavo did with his column.

Gustavo Arellano: The point of Ask A Mexican was always to debunk and deconstruct stereotypes and misconceptions about Mexicans in a way that educated, infuriated and entertained. And it was all the whole point of asking Mexican was always to punch up, never down.

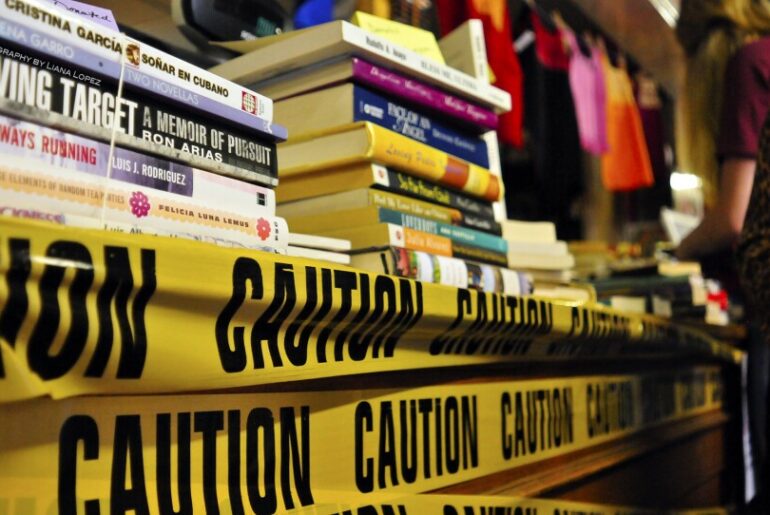

Liz Alarcón: The Column ran from 2004 to 2017. Gustavo compiled all his favorite questions through the years into a book, titled, you guessed it, Ask A Mexican. Today, Gustavo Arellano is a staff writer at the LA times and host of their daily podcast. You can find his newsletter at GustavoArellano.org