On June 15, 2012, President Barack Obama stood in the White House Rose Garden and announced a new program that would transform the lives of hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children.

The program was called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), and it was, at the time, seen as a temporary solution to provide relief to immigrant youths who arrived in this country with their parents. Before DACA, deferred action — a deal by the government to not deport a noncitizen — was rarely granted. Still, it does not provide a pathway to citizenship for recipients.

In the past decade, more than 800,000 people have benefited from DACA’s shield of protection from deportation and access to work permits. In addition to having broader access to higher education and more job opportunities, DACA holders have been able to set down roots with some temporary protections in place.

Kassandra Carrasco-Gonzalez is the assistant director for the Hispanic/Latinx and Gender and Sexuality Resource Centers at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. When she first came to the U.S. as a child, she lived with the fear of deportation looming over her and her family — that is, until DACA was implemented in 2012.

“All of a sudden, I was protected,” Carrasco-Gonzalez told Rocky Mountain PBS. “All of a sudden I felt more comfortable and more confident.”

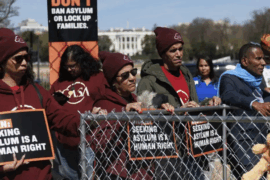

Still, immigration advocates say DACA is not enough and more needs to be done to guarantee protections and citizenship status in the future.

United We Dream has organized demonstrations today, calling for “citizenship for everyone in our communities,” and affirming “Our home is here!” The organization is the largest immigrant youth-led network in the country. To support their efforts, donations can be made at unitedwedream.org.

For those who need help paying DACA fees, Voto Latino says “we want to help make the journey a little easier.” Email [email protected] for financial support.