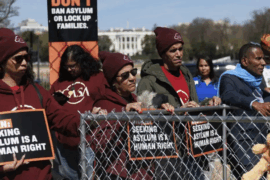

Last week, immigrants protested on Capitol Hill to show support for a bill that could provide Dreamers with a path to citizenship. The American Dream and Promise Act was passed by the House of Representatives on March 18, and now awaits a vote in the Senate. While the bill is new, the fight is not, and activism is mounting.

Today, there are more than 3 million Dreamers — undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children — living in the country. The name “Dreamers” comes from a 2001 bill known as the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, otherwise known as the DREAM Act. The bill aimed to solve the issue of providing the right to work, and eventually a path to permanent residency, to those who entered the U.S. as youths. It never passed.

In 2012, then-President Barack Obama announced his administration would stop deporting Dreamers under a new Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. More than 800,000 people had received protection under DACA. Following Obama, then-President Donald Trump terminated DACA, thus ending Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure programs. This meant that people who came to the U.S. as minors, even as babies, were considered ”priority for deportation.”

Now, the American Dream and Promise Act, supported by President Joe Biden, seeks to give broad protection to 2.5 million out of the 3 million Dreamers. It covers anyone who arrived in the U.S. before turning 18, has been in the U.S. for four years, is not a felon, has a high school diploma or GED certificate, and passes a background check.

Although it was approved by the House with some Republican support, political analysts are unsure the bill will end up on the president’s desk. For more than a decade, similar bills have died in the Senate, and this time may be no different.

That hasn’t stopped organizers like Cecilia Martinez — a mother of two who has Temporary Protection Status — from pushing to get it passed. Last week, she took to the streets of the nation’s capital to put pressure on the country’s leaders.

“We have over 50 communities of TPS and have marched several times in Washington, D.C,. and spoke to Congress,” she said. “We have been in the rain, in the wind; nothing has been able to stop our movement.”

While the American Dream and Promise Act would support those who did not necessarily have a choice when entering the country, a more bold immigration policy that protects all 11 million people living without citizenship will not realistically pass through the current Congress. Shortly after being inaugurated, Biden proposed an immigration overhaul to provide a pathway to citizens to all immigrants in the U.S. Republicans scrapped it immediately.

Regardless of such losses, some remain optimistic. Sarahi Aguilera is a Dreamer who joined a demonstration in D.C. to support the Dream and Promise Act. While she says the past four years have been draining, she still has hope that the current administration will accomplish some change. “I know this bill would not impact all 11 million undocumented immigrants in this country, but it’s small victories like such that fuels the community to continue advocating and organizing,” she said.

The American Dream and Promise Act needs 60 votes to pass the Senate, where Democrats hold 50 seats.