The Biden administration unveiled a highly anticipated immigration bill last week. If passed, it would become the first major citizenship law since 1986. Among the policies proposed are legislation for an eight-year pathway to citizenship, a shorter legal status for agriculture workers, and new enforcement measures for border patrol technology.

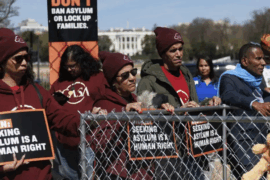

Also central to Biden’s immigrations plans is the removal of obstacles to asylum, which is a largely contested issue due to the Trump administration’s handling of immigrants fleeing political turmoil and disasters in their home countries. For Central American immigrants in particular, who have had an especially difficult four years with restrictions on asylum processing, these new policies have potential to mark a new era in immigration law. The Biden administration said, on Feb. 19, it would begin allowing 25,000 people at the border seeking asylum into the U.S.

The decision comes as a result of a Trump-era policy, from which thousands of migrants were forced to stay in Mexico until their court date. This means that families and individuals were subjected to often dangerous conditions for months before a hearing. While in Mexico, some migrants were targets of violence and have faced threat of extortion, sexual assault and kidnapping.

The Biden administration has identified three ports along the border that will process individuals. Two of the three ports, once fully operational, can potentially serve 300 individuals daily. According to a recent report by UT Austin, Customs and Border Patrol has sent more than 68,000 asylum seekers to Mexico, but “there are only 22,777 pending cases” along the border.

While the Biden Administration continues plowing ahead with statements on the new policies, there is no clear deadline. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorka stated that “changes will take time,” because of challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic. He also clarified that those who are not eligible for entering the U.S. should not travel to the border at this time.

For some immigrant activists, the murky details of these policies raise flags. Luis Angel Reyes Savalza is the co-director of Pangea Legal Services, a San Francisco-area nonprofit that provides legal support for undocumented immigrants. “They’re using immigrants as political bargaining chips,” he said. “It’s too little, too late.”

Yurina Guzmán, an undocumented immigrant volunteering with Papeles Para Todos, agrees with the sentiment that these reforms are not clear or strong enough. She also does not trust the new administration because she feels Democrats have historically broken their promises to enact immigration reform. “For many many years, we have been lied to,” Guzmán said. “The [immigration] reforms are going to be in limbo … I don’t trust anything right now.”

After months that have stretched into years in some cases, some waiting in Mexico are uncertain of their future. “I don’t know if this president will come through on his policies, but at least we might have a better future,” said one 30-year-old Cuban migrant, who has been waiting at the border for a year and a half. “We’re very, very desperate. We’ve been here for a long time.”