It’s been over one month since Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) on March 18, which aimed to help those who work in companies with less than 500 people afford to stay home during the coronavirus pandemic. In the past month, we’ve seen how the act has fallen short in supporting working-class and poor Latinos, especially those employed at companies like Amazon, with over 500 employees.

The FFCRA gives full-time and part-time workers up to two additional weeks of “emergency sick time,” in an effort to ensure people stay home if they have contracted the virus. It also seeks to help those who miss time working, have to take time for childcare, or experience loss of income due to the coronavirus. But because of the nature of the national labor force, the majority of Latinos cannot realistically work from home because many are in service fields or deemed “essential.”

The concept of an “essential worker” has been used since the beginning of the country-wide restrictions, when many workers were not afforded the privilege of following Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommendations and staying home to avoid spreading coronavirus. Amazon workers for example, had to deliver goods across the country and are not covered by this act.

While FFCRA covers people who work at companies with less than 500 employees, it leaves out those who need it but work at larger companies like Walmart, which employs 1.5 million in the U.S. alone. A 2017 study found that over 36% of the U.S. population worked in corporations with over 1,000 people, making them exempt from being offered the additional two weeks of sick time. And what’s more, the act does nothing to protect the estimated 3 million workers who will lose their jobs by the summer.

In the month since this law was passed, more data has uncovered how Latinos are amongst the most affected by this virus. These findings bode poorly with the law’s exclusion of so many people, especially Latinos and undocumented people who often hold blue-collar jobs in the food industry without health benefits.

Beyond grocery stores and restaurants, the act and its holes have intense repercussions for other workers. Someone working at a Starbucks inside of a Target, for example, could be expected to go into work, even though their Starbucks operations were non-essential.

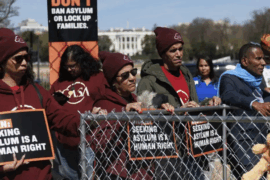

Workers across the country have protested the lack of financial support from their employers and planned a historic mass strike on May 1, or “May Day.” One of the organizers is Chris Smalls, who was fired from Amazon in what many see as retaliation for organizing a walk-out at the warehouse where he worked. He says that it’s important now more than ever to have consumers and employees “On the same side. We are doing a service for the consumers, but if we’re not healthy, we’re doing a disservice. Meaning we’re bringing this virus back to the communities.”