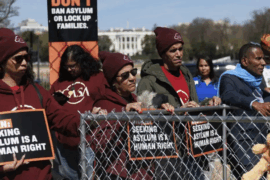

People are prosecuted for illegal entry or reentry into the United States, but few employers are ever punished following ICE raids. During the 2019 Mississippi ICE sting, 680 undocumented immigrants were detained. Photo: formulanone from Huntsville, United States, MS25 North – Carthage Sign (39877322860), CC BY-SA 2.0

Six months after a coordinated statewide immigration sting, some businesses are still suffering throughout Mississippi. The largest single-state worksite sting in U.S. history left businesses without workers, dwindling clientele, and a community looking to its neighbors for help.

Today, communities are still reeling from socio-economic despair following the Aug. 7 detainment last year of 680 undocumented workers at Mississippi food processing plants by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in Carthage, Canton, Walnut Grove, Pelahatchie, Forest, and Morton.

The once-thriving processing plants in towns like Morton have suffered a shrunken workforce that was mostly comprised of Latino laborers. “You don’t replace those people that easily, number one. Number two, it’s hard work,” Tito Eshiburu, Morton banking executive, said. “Hispanics have filled that void and they have worked there for years, and so it’s been hard for [the companies] to replace them.”

Photo: Bloomberg, Getty Images.

Replacing Latino workers is easier said than done for employers paying low wages while expecting laborers to work long hours in grueling conditions. Koch Foods has been forced to settle $3.75 million in harassment and intimidation claims made by plant workers who say they were threatened with deportation, verbally abused, and physically assaulted.

Since the game-changing ICE raids occured late last summer, none of the processing plant companies’ executives at businesses like Peco Foods and Koch Foods have been charged for hiring undocumented workers.

According to an analysis by Syracuse University, few employers are ever punished following ICE raids. From April 2018 to March 2019, only 11 employers throughout the country were prosecuted for hiring undocumented workers. During this same time period, over 120,000 people were prosecuted for illegal entry or re-entry into the United States, often looking to find jobs at worksites like the processing plants in Mississippi.

Local churches, like First United Methodist Church of Morton, have started food pantries to distribute food and groceries to families and provide utility bill assistance and housing for the destitute. Families of loved ones detained in the sting have been left to cope with their new realities as some household breadwinners remain in detention or have been deported.

“Well, when we opened the food pantry that week that the ICE raids happened we assisted 236 families with food that week,” Rev. Sheila Cumbest, pastor of First United Methodist Church, said “Now we are assisting around 120-125 families still with food, and utilities, and housing.”

While the small Mississippi towns attempt to recover the once bustling dynamics of their neighborhoods, residents are still fearful. “What was the neighborhood like before all this happened? More happy,” Patricia Naguera, owner of Morton grocery store El Mercadito, said. The small business owner attests that her neighbors only leave their home to buy essential food and groceries, afraid to step out into their own neighborhoods.