January marks Human Trafficking Awareness Month, and January 11 is national day of human trafficking, designated to reaffirm a commitment to stop modern slavery and trafficking. While the vast majority of cases reported are related to sex exploitation, trafficking happens whenever an employer uses force, fraud or coercion to maintain control over the worker.

It turns out, seasonal farmworkers in the U.S., mostly consisting of Latin American men, women and children, frequently face this type of exploitation. Their vulnerability in citizenship status, not speaking fluent English, and isolation often aids the forced servitude.

One particular report published by the State Department in 2015, made a point of giving special attention to the problem of agricultural labor rights all along the global supply chains of food industries. A year later, Verité, a global non-governmental organization committed to research labor issues along with the U.S. Department of State, released a report that detailed the imbalance between workers and employees in the international agricultural sector.

One of the main take-aways of this report was the need for “labor brokers,” the middle men required in global supply chains who act as intermediaries between workers and management. These labor brokers often promise victims high salaries and excellent conditions, but charge recruitment fees and charges for passport and visa processing), which leaves the worker in debt to the agency.

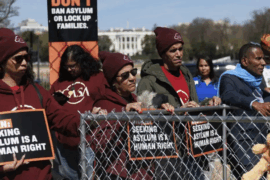

This debt-bondage is at the core of many human rights abuses that affect agricultural communities. Since victims are often also undocumented, or working with temporary H-2A work visas, which allow them to fill temporary agricultural jobs, they are at higher risk and are more vulnerable. The limited access to legal systems, dependence on the employer to maintain legal status, and necessity to send remittances to their home country amplify exploitation, according to the Verité report. These factors result in forced labor and are amplified by “the discrimination and xenophobia that migrants are increasingly facing everywhere,” according to the report.

Issues of language, legal status and lack of access to legal systems were highlighted by a profile of a case, published in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, which detailed the exploitative conditions of a Borzynski Farms in Wisconsin. The farm was under federal investigation after the Department of Workforce Development (DWD) received a tip that it was “holding workers like prisoners.” This case is a recent example of public legal retaliation, but cases like this often go “unnoted or not officially investigated,” according to an assessment released by the Department of Justice.

The Department of Agriculture estimates that half of the nation’s farmworkers are unauthorized, which means that a rise in mass-deportations does not only affects the lives of hundreds of thousands of workers, and also poses a threat to the agricultural industry. In December 2019, the Farm Workforce Modernization Act passed the U.S. House with bipartisan support. The bill would streamline the H-2A agricultural visa program, cutting bureaucracy and providing a path to legal citizenship for undocumented agriculural workers.

As the act heads to the Senate for a vote, it stands out as the first bill to address agricultural labor since 1986, but has been contested within some immigrant and farmworker advocacy groups for not providing sufficient protection to the workers, and “giving employers all the power.” Regardless of the outcome of the vote, lack of attention of human trafficking of farm workers is detrimental to Latino communities, whose hands harvest our nation’s food.