Octavio Solis: Every time we remember something, we remember it less clearly. We’re a different person. You never cross into the same stream twice. So every time you go and revisit that memory, something else jumps out at you that you hadn’t seen before, and you don’t know any more what’s true. You don’t know anymore what’s real.

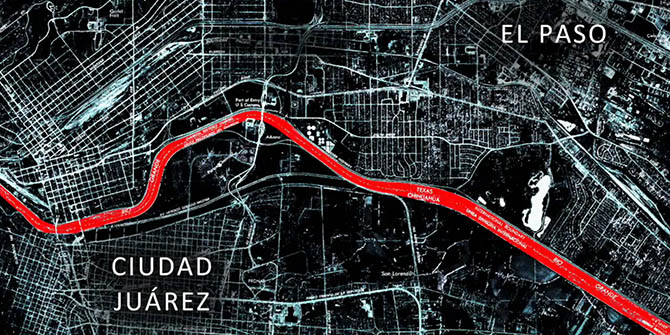

Narration: A Retablo is a devotional painting, a rudimetnary piece of art scrawled on a sheet of metal or wood, all to hold a memory or to commemorate a sacred event, like a miracle, an answer to a prayer, or sometimes it’s a darker memory, like a trauma, calamity, or death. A retablo is a kind of postcard to God, it’s an attempt to memorialize a moment, to hold onto a memory as our own recollection begins to fade and dim. Playwrite Octavio Solis grew up along the US-Mexican border, If you asked him where he’s from he would say El Paso Texas, just across the river from Juarez Mexico where his parents were from.

Octavio Solis: I was born of immigrant parents in El Paso, Texas back in 1958. And raised there, literally half a mile from the Rio Grande at a time before there was a border freeway, before there was a wall there. My identity is tied up with that border.

Narration: He spent his childhood like many kids do in the US, playing with friends, racing on his bicycyle and occiasinally getting into some trouble, but unlike most kids in the US he grew up with an acute understanding of the reality that existed along border, of the chasim that was created by that little line in the sand. It was daily occurance to see migrants crossing over, searching for better opportunities, just like his parents had years before, but there was always something that seperated him from those crossing over. They looked the same, they could speak the same language, but there was always some kind of barrier between them. It also felt this way when he would go across the River to Juarez each month with his family, where it was similar but also unmistakable different, The smells, the energy, something changed when that invisible line was crossed. After Highschool he was ready to leave his past behind, he went off to study literature in Dallas, then in England. He left El Paso, but El Paso never left him, because as he built his career writing plays about life along the border, while he would be writing deep into the night, that’s when he would feel his childhood memories creeping back

Octavio Solis: 2, 2 30 in the morning, I remember something from my childhood. And I’d go, you know, I better write that down before I forget it, because it’s just weird and dreamlike enough that it might be an idea for a play down the line. But I said for right now, this is just for me.

Narration: As these dreamlike childhood memories crept back into his consciousness, Octavio would capture them on the page, one by one . These hazy, ghostlike scenes became memorialized on the paper, not so different from the retablos of old, painted on tin sheet or a carved into a piece of wood. These memories eventually found their way into a book. And today we have two stories from octavio, two of his hazy memories, two of his childhood dreams, two of his retablos. I first discovered Ocatvios book of retablos a few years ago, a chance encounter on the internet…, as I read, one passage that struck me was called La Migra, the story of one of Octavio’s encounters with border patrol. I asked him about this.

Octavio Solis: We saw them every day. We saw them every day driving around, looking for people or just patrolling the area, and then we’d see some people that would be crossing over. That we knew were different from us, but look so much like us. And we’d help him in, in ways that were devious on our part when they’d stop us, we’d say, oh, did you see someone walk this way? And we’d say, no, no. We saw them walk the other way. We saw him walk that way. And I think there was a sense that it was troubling because they look like us. And yet we, we were more privileged. But that line was erased whenever they stopped us and asked us for identification. It was like, oh man, there’s nothing separating me from those people. I am those people. It’s just that as kids, we didn’t really understand that until it started happening and then it got scary. I become powerless, in the face of power.

CG: Here’s Octavio’s story, La Migra.

Octavio Solis: La Migra, that’s what we call them. That’s how I have always known them. It’s a derogatory term, but we don’t even think of it like that. It’s just what they are. Ever since we moved into the lower valley, the green and white cruisers of the border patrol have been everyday fixtures in our lives. In the early days, they are older guys who take their jobs in stride. They ride them patrol like hired Cowboys roping in the errand doggies, or maybe more like Texas Rangers patrolling the wild frontier. They know a large portion of the migrants who slipped through their net, and they know many of those they catch will be back through a fence in a matter of days. They’re philosophical about their mission.

What’s the harm in a few “mojados” coming in through? They’re philosophical about their mission. What’s the harm in a few “mojados” coming through? Don’t we need the manpower anyway? Then in the late sixties and early seventies, there was a new breed of officer, stern, all American types, ex soldiers who got their asses kicked in the jungles of Vietnam. And now look to settle that score with these wetbacks and their smuggled marriages. They take the top seriously, consider themselves a cut above the average city cop. What they do is harder and it makes a bigger difference in the complicated world of “La Frontera”. That’s my take on the many way I started noticing something else in the early seventies though.

Maybe it was always there and I just didn’t see it. Or maybe it’s the result of the recession and the lack of good paying jobs. Suddenly, there are more Chicanos manning the vans and cruisers. The iron in the faces, the edge in the eyes. It’s all the same on the, now the faces and eyes are brown. The badges say Marquez, Armendariz, Lujan. Some are even rougher than the Wrangler counterparts. It doesn’t matter that their parents probably came over the same river with the same intention. One generation is all it takes to keep the past and the legacy of their migration at bay. They’re American now, and this is how they show it. We’re used to them, how they slow down whenever we’re outside drinking Cokes on our bikes, the officer in his aviator sunglasses looks us over scouring our skinny bodies for the one thing that marks us as foreign.

Kino and I point to each other and mouth the words, take him, take him. My sister takes exception though. She thinks the border cop is checking her out and she’s probably right. But the fact that he’s even scrutinizing us this closely is disturbing his look lingers just long enough to make us feel like strangers to ourselves, all the “mojaditos” that we generally scowl at when we spy them tramping, restlessly past our house. He’s consciously connecting them to us. We’re nothing like them. We’ve conditioned ourselves to say we’re legal born on this side, but the border cop with a steady gaze is telling us with this look that the distinction is very thin, thin as the lenses and as aviators. Thin as a line on a map. This day, I am waiting for the bus to take me downtown, to see a movie. The bus stop is just across the street from my house. The border patrol comes up the street and stops right at the curb. It’s that Mexican officer again, and he’s wearing the same reflective sheet.

His partner is this white guy who looks like he’s been badly sunburned. Both of them are giving me a once-over that makes me nervous. It’s the Mexican who talks to me. You seen anyone go by here lately? No. Anyone wearing a red tee? No, you’re wearing a red tee. I looked down at myself and look at the red t-shirt with the lettering of some band I used to think was bitchin’. Where you from, kid? he asks. Here. Where? America. Where do you live? Right there. I pointed my house. What’s the address I recited for him. Like my life depends on it. Then he does something unexpected. He removes his shades and asks me, “hablas Español?” Now I’m trapped. I want to say no, even if it’s a lie, because to admit that I speak Spanish would put me in the other guy’s red tee. Just like that, he’s made me ashamed of my original tongue, forced me to deny my father’s language and thereby denied my father and his father’s before him. And the crazy thing about it is this man is using that very same Spanish against me. There’s only one thing I can say.

What? You know what I said. No, sir. He smirks at my lie and looks me right in the face. Do you want to spend your days over there? I’m an American sir. Barely. Where are you going? The movies? In my peripheral vision, I sense my mom at the front door and the white officer nudges, his partner who puts on his aviators and tells me to keep an eye out for a mojado with a red t-shirt, which is what I see reflected in the lenses. If you spot him, you call us, okay? These guys are the butts of our jokes. Now they have me shaking. They say, have a good day and drive on down the street. The bus comes right after they leave. And I go to my James Bond double bill at the palace theater downtown, and the whole time I’m watching the screen, I am hating these men and thanking them at the same time because they’re right. I am the guy in the red tee I am him. And he is me.

CG: Another of Octavio’s Retablos that I fell in love with was Jeep In The Water, the story of a drug smugglers jeep abandoned in the middle of Rio Grand as it tried to cross, and the battle that followed when both countries wanted what was inside.

Octavio Solis: Someone told me a story. He said, someone told me this. And then I heard from somebody else I heard from somebody, they told me this story. I don’t know that it’s even true, but because it sounds true and because it sounds like a big lie. It belongs in the domain of legend. I said, okay, let me tell this story about how this tug of war for a Jeep, really represents a tug of war that’s going on inside of us, who straddle that hyphen the river or the border for us? There’s still a lot of me that is on the other side. And I feel the tug of one side or the other for control of my soul. There’s, there’s a lot about the Jeep that feels like it’s me.

CG: Here’s, Jeep in the water

Octavio Solis: The Rio Grande, we call it on the us side. Rio Bravo is what they call it in Mexico. The difference is the difference.

Somewhere in the murky depths of this beleaguered band of water is a demarcation line, invisible to all, but the respective governments of both nations. One morning, a long time ago, which in El Paso could mean neither 50 years ago or yesterday two border patrol field agents on their round spot, a dealer fresh cherry red Jeep parked in the shallow Rio. It’s unattended right in the center, the brown water coursing halfway up the doors loaded with kilos of marijuana upon inspection. The agents surmise that some audacious drug runners from war is somehow got it into their “cabezas” that if they had the right vehicle, they could simply drive through the river at its shallowest point and safely transport their cargo to its destination. It almost worked. They probably felt like geniuses as their Jeep readily churned through the water in the dead of night.

But right at midstream with no horses to jump to the Jeep had come to a gurgling halt, mired and deep silty slow. The dried spreaders of mode and the shiny red exterior suggest to the agents, some recent, desperate heaving back and forth of the vehicle. Apparently the deflated smugglers abandoned their mission and waded back to Juárez, sans mary jane. Pleased with their catch, the border patrol field agents notify their superiors and summon a tow truck to drag the Jeep to shore. By now, a small crowd of people has gathered on both sides of the river to GOC, alerted to the spectacle by the traffic choppers of morning radio. The congregations seem harmless enough, more bemused in alarm that the side of a stranded Jeep in the middle of the river.

So the agents take on the standard cursory notice the tow truck appears on the scene in due time. And the young attendant begins running a long tow line to the Jeep. That’s when things take an ugly turn. Before he can reach the vehicle he’s being pelted by the Juárez assembly with stone, slabs of concrete, bottles and whatever else is handy. And he’s driven back out of the water. The agents shout admonitions to the suddenly bristling mob. But at that moment, a tow truck on the Mexican side backs up to the bank and two men charged into the river with their own toll. This brazen act, afford some incentive to the border patrol toll man. And he barrels back into the water.

An uproar of curses rises from both sides of the river in two languages, as the men slosh like lunatics to the Jeep with their tow lines. The Mexicans secure theirs to the rear fender of the Jeep, while the American ties his to the front. Then the contest begins. The tow trucks rev their engines, pull the toll lines, taut and proceed to pull on the Jeep in opposite directions, an international tug of war commences with great noise and cheering from the gathered spectators, many of them already picnicking on the promontories with churros and beer. Back and forth lurches the Jeep, first toward Mexico, then toward the US, then back Mexico way. Wagers are taken on who will prevail. Some brave boys even grab the line and tug hard to stack the odds in Juárez’s favor. The border patrol, fire warning shots in the air to disperse the crowd and demand the tow truck desperadoes cease their criminal acts. But it’s no use. Nobody can hear the shots above the shouting and the clamor of the news choppers directly overhead.

This is now a full blown international. At long last, a larger, heavy duty tow behemoth designed for hauling 18 wheelers pulls up to the U S embankment and it seasoned driver long in the tooth and short in the saddle dodging various projectiles succeeds in attaching his own tow line to the derelict Jeep. Once ashoer, he climbs into his cab and sets to towing it out of the water. The crowds fall silent as a steel cable tautens. Señor Jeep heaves mournfully for a moment over the loud grind of the overheating engine of the Mexican tow truck, then a hideous crunch is heard as the rear fender snaps off and flies into the air, like a catfish being reeled in. To cheers from the Americans and jeers from the Mexicans, the Jeep slowly taxis northward to America. But not before some daring, half naked Mexican kids rush to snatch some bags apart, souvenirs of this mighty Pan- American match. The Jeep is impounded, the marijuana seized, displayed, and detroyed.

And the story widely circulated for a time throughout the Southwest with many, a chuckle is eventually forgotten in the mix of more sensational and blurrier stories of the war on drugs, bedeviling the region. But somewhere below the surface of this river, covered over by the silt of years, like the footprints of an ancient dynasty, lyceum print of tire tracks from a solitary Jeep that challenged the legitimacy of this invisible line we call the border.

CG: You can find more of octavios stories in his book Retablos, from City Lights Publishers. This episode was produced & sound designed by me Charlie Garcia, audio editing & music by Julian Blackmore, editorial oversight by Liz Alarcón.